by Noah's Ark | Apr 30, 2020 | Animals, Climate Action, Climate Change, Conservation, Global, Natural World |

The whole world has been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic – we all fear for our own health, that of our loved ones and also those who are most vulnerable. In the span of just a few weeks, Covid-19 suddenly become more urgent than the crises of ongoing climate change or the dangerous decline in biodiversity. Catastrophic events that once monopolised world attention, such as the forest fires in Australia , suddenly seemed less serious than a pandemic that could touch all of us, immediately, in our own homes.

However, like other major epidemics (AIDS, Ebola, SARS, etc.), the emergence of the coronavirus is not unrelated to the climate and biodiversity crises we are experiencing. What do these pandemics tell us about the state of biodiversity?

New pathogens

Humankind is destroying natural environments at an accelerating rate. Between 1980 and 2000, more than 100 million hectares of tropical forest were felled, and more than 85% of wetlands have been destroyed since the start of the industrial era. In so doing, we put human populations, often in precarious health, in contact with new pathogens. The disease reservoirs are wild animals usually restricted to environments in which humans are almost entirely absent or who live in small, isolated populations.

Due to the destruction of the forests, the villagers settled on the edge of deforested zones hunt wild animals and send infected meat to cities – this is how Ebola found its way to major human centres. So-called bushmeat is even exported to other countries to meet the demand of expatriates and thus spreads the health risk far from remote areas.

We shamelessly hunt exotic and wild species for purely recreational reasons – the appeal of rare species , exotic meals, naive pharmacopeia, etc. The trade in rare animals feeds the markets and in turn leads to the contamination of urban centres by new maladies. The epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) rose out of the proximity between bats, carnivores and gullible human consumers. In 2007, a major scientific article stated:

This time bomb seems to have exploded in November 2019 with the Covid-19.

The danger of zoonoses

The consumption and import/export of exotic animals have two major consequences. First, they increase the risk of an epidemic by putting us in contact with rare infectious agents. While they’re often specialized by species and thus cannot defeat our immune system or even penetrate and use our cells, trafficking and confinement of diverse wild animals together allows infectious agents to recombine and cross the barrier between species. This was the case for SARS and may have been the case for Covid-19 . Beyond the current crisis, this risk is not marginal: It should be remembered that more than two-thirds of emerging diseases are zoonoses , infectious agents that can pass between animals and humans. Of these, the majority comes from wild animals.

Second, capturing and selling exotic animals puts enormous pressure on wild populations. This is the case with the pangolin , recently brought to light by the Covid-19 pandemic. The eight species of this mammal, which is found in Africa and Asia, are poached for their meat and scales despite their protected status. More than 20 tonnes of meat are seized each year by customs, leading to an estimate of around 200,000 individuals killed each year for this traffic.

Humanity is thus doubly endangering itself: We are enabling the creation of emerging diseases and also destroying the fragile biodiversity that provides natural services from which we benefit.

The circumstances of the emergence of these new diseases can be even more complex. This is how Zika and dengue viruses are transmitted by exotic mosquitoes transported by humans through international trade. The trade in used tires in which water collects and allows aquatic mosquito larvae to develop and be transported is particularly criticized. Here the disease does not spread by a first direct contact between the human species and reservoir animals followed by intra-human transmission, but it is transmitted to the human species by vector mosquitoes, the latter moving efficiently with our help.

Managing human and environmental health

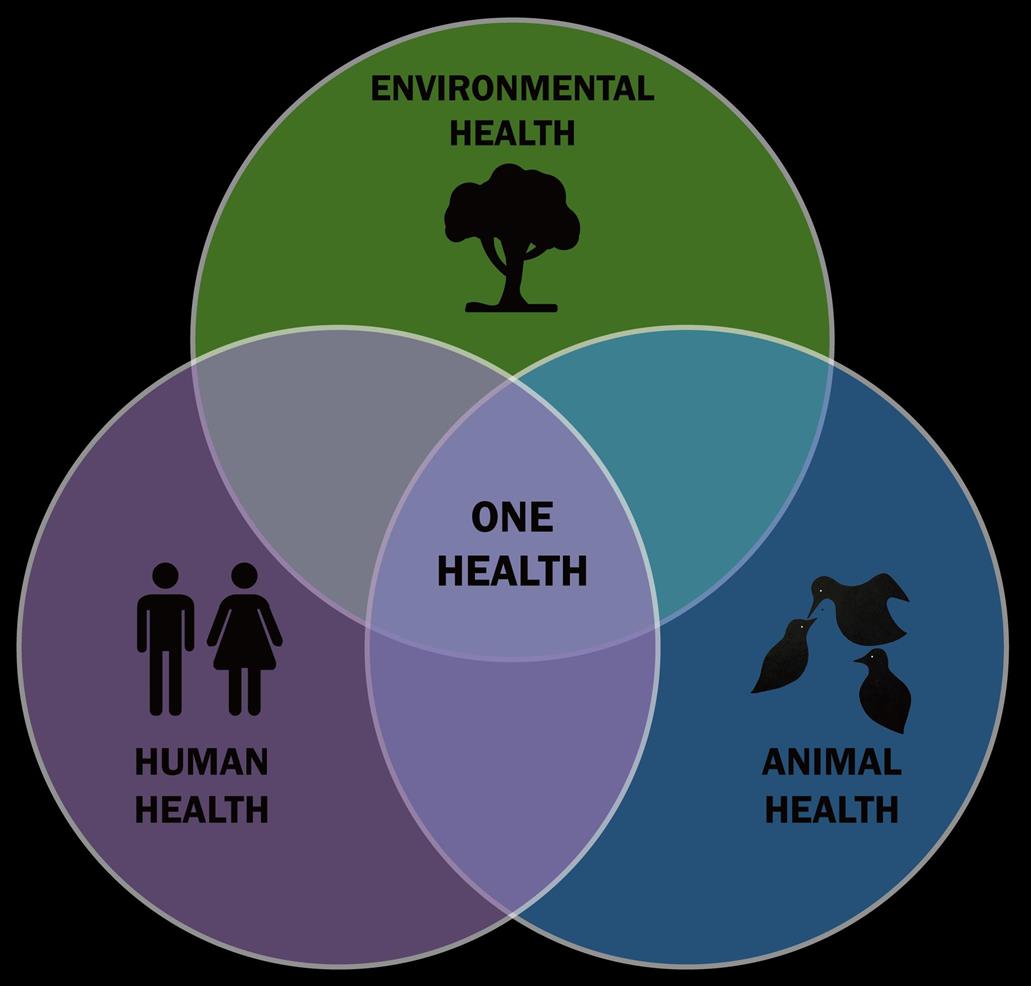

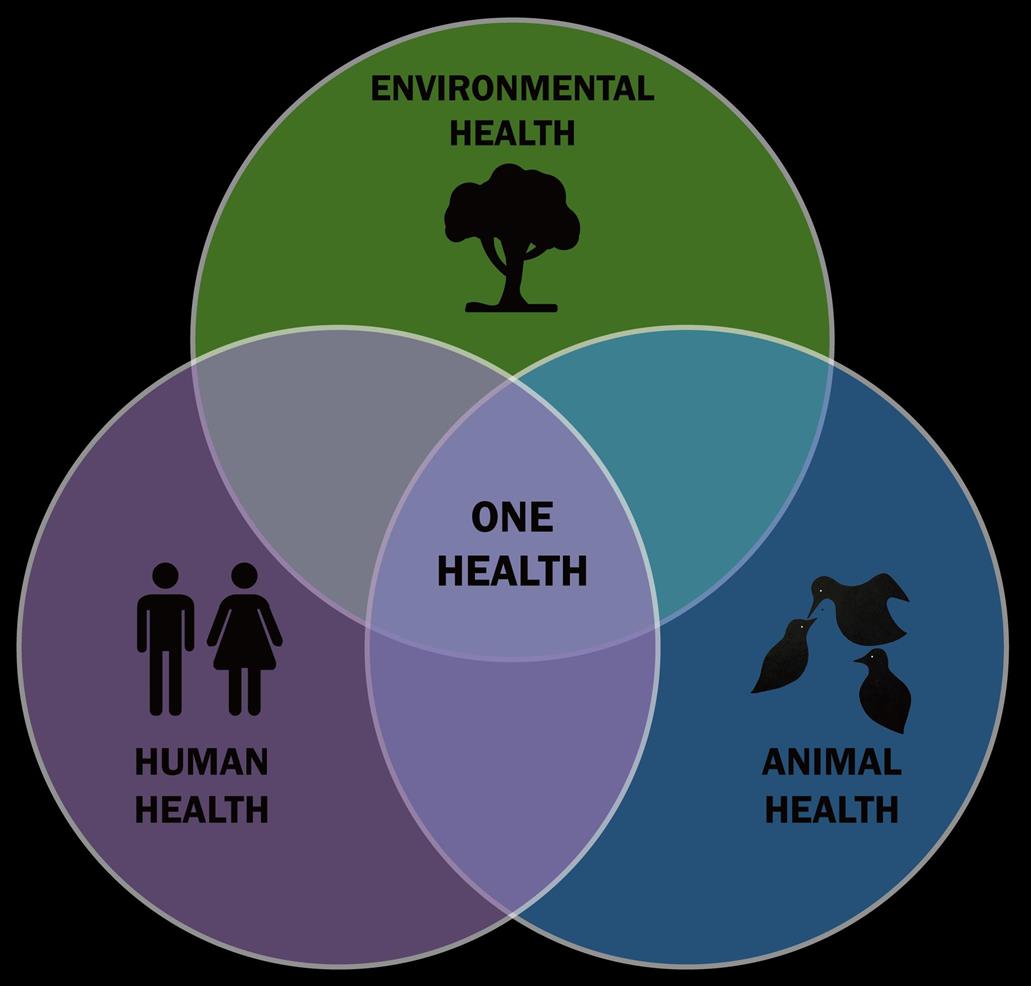

The World Health Organization’s ‘One Health’ initiative advocates managing the issue of human health in relation to the environment and biodiversity. It has three main objectives: combating zoonoses, ensuring food safety and fighting antibiotic resistance.

The ‘One Health’ initiative seeks to promote optimal health for people, animals and the environment. Wikipedia

This initiative reminds us that we cannot live in an artificial cocoon, never be in contact with biodiversity whether it be wild, raised or grown. Two of the initiative’s three targets – food security and zoonoses – are directly related to the current Covid-19 crisis. We should not create dangerously unsustainable food circuits, whether it be importing exotic species or feeding unnatural products to farm animals – this was what led to mad cow disease , after all.

The causes of the biodiversity crisis are well known and so are the remedies. First and foremost is stopping the destruction of the environment – deforestation, the world trade in any commodity or living species, the transport of exotic animals – for short-term gain, often just a few percentage points of profitability compared to local production.

The world after Covid-19

Voices are starting to be heard that that the ‘world will not be the same after Covid-19’ . So let’s integrate into this ‘next world’ a greater respect for biodiversity. It’s our greatest immediate benefit!

The world that we will leave to our children and grandchildren will experience deadly new pandemics , that is unfortunately certain. How many will there be depends on our efforts to preserve biodiversity and natural balances, everywhere on the planet. Beyond the current human tragedies, one can at least hope that Covid-19 has had the positive effect of raising this awareness.

by Noah's Ark | Mar 30, 2020 | Animals, Conservation, Global |

A strict ban on the consumption and farming of wild animals is being rolled out across China in the wake of the deadly coronavirus epidemic, which is believed to have started at a wildlife market in Wuhan.

Although it is unclear which animal transferred the virus to humans — bat, snake and pangolin have all been suggested — China has acknowledged it needs to bring its lucrative wildlife industry under control if it is to prevent another outbreak.

In late February, it slapped a temporary ban on all farming and consumption of “terrestrial wildlife of important ecological, scientific and social value,” which is expected to be signed into law later this year.

But ending the trade will be hard. The cultural roots of China’s use of wild animals run deep, not just for food but also for traditional medicine, clothing, ornaments and even pets.

This isn’t the first time Chinese officials have tried to contain the trade. In 2003, civets — mongoose-type creatures — were banned and culled in large numbers after it was discovered they likely transferred the SARS virus to humans. The selling of snakes was also briefly banned in Guangzhou after the SARS outbreak.

But today dishes using the animals are still eaten in parts of China.

Public health experts say the ban is an important first step, but are calling on Beijing to seize this crucial opportunity to close loopholes — such as the use of wild animals in traditional Chinese medicine — and begin to change cultural attitudes in China around consuming wildlife.

Markets with exotic animals

The Wuhan seafood market at the centre of the novel coronavirus outbreak was selling a lot more than fish.

Snakes, raccoon dogs, porcupines and deer were just some of the species crammed inside cages, side by side with shoppers and store owners, according to footage obtained by CNN. Some animals were filmed being slaughtered in the market in front of customers. CNN hasn’t been able to independently verify the footage, which was posted to Weibo by a concerned citizen, and has since been deleted by government censors.

It is somewhere in this mass of wildlife that scientists believe the novel coronavirus likely first spread to humans. The disease has now infected more than 94,000 people and killed more than 3,200 around the world.

The Wuhan market was not unusual. Across mainland China, hundreds of similar markets offer a wide range of exotic animals for a range of purposes.

The danger of an outbreak comes when many exotic animals from different environments are kept in close proximity.

“These animals have their own viruses,” said Hong Kong University virologist professor Leo Poon. “These viruses can jump from one species to another species, then that species may become an amplifier, which increases the amount of virus in the wet market substantially.”

When a large number of people visit markets selling these animals each day, Poon said the risk of the virus jumping to humans rises sharply.

Poon was one of the first scientists to decode the SARS coronavirus during the epidemic in 2003. It was linked to civet cats kept for food in a Guangzhou market, but Poon said researchers still wonder whether SARS was transmitted to the cats from another species.

“(Farmed civet cats) didn’t have the virus, suggesting they acquired it in the markets from another animal,” he said.

Strength and status

Annie Huang, a 24-year-old college student from southern Guangxi province, said she and her family regularly visit restaurants that serve wild animals.

She said eating wildlife, such as boar and peacock, is considered good for your health, because diners also absorb the animals’ physical strength and resilience.

Exotic animals can also be an important status symbol. “Wild animals are expensive. If you treat somebody with wild animals, it will be considered that you’re paying tribute,” she said. A single peacock can cost as much as 800 yuan ($144).

Huang asked to use a pseudonym when speaking about the newly-illegal trade because of her views on eating wild animals.

She said she doubted the ban would be effective in the long run. “The trade might lay low for a few months … but after a while, probably in a few months, people would very possibly come back again,” she said

Beijing hasn’t released a full list of the wild animals included in the ban, but the current Wildlife Protection Law gives some clues as to what could be banned. That law classifies wolves, civet cats and partridges as wildlife, and states that authorities “should take measures” to protect them, with little information on specific restrictions.

The new ban makes exemptions for “livestock,” and in the wake of the ruling animals including pigeons and rabbits are being reclassified as livestock to allow their trade to continue.

Billion-dollar industry

Attempts to control the spread of diseases are also hindered by the fact that the industry for exotic animals in China, especially wild ones, is enormous.

A government-sponsored report in 2017 by the Chinese Academy of Engineering found the country’s wildlife trade was worth more than $73 billion and employed more than one million people.

Since the virus hit in December, almost 20,000 wildlife farms across seven Chinese provinces have been shut down or put under quarantine, including breeders specializing in peacocks, foxes, deer and turtles, according to local government press releases.

It isn’t clear what effect the ban might have on the industry’s future — but there are signs China’s population may have already been turning away from eating wild animals even before the epidemic.

A study by Beijing Normal University and the China Wildlife Conservation Association in 2012, found that in China’s major cities, a third of people had used wild animals in their lifetime for food, medicine or clothing — only slightly less than in their previous survey in 2004.

However, the researchers also found that just over 52% of total respondents agreed that wildlife should not be consumed. It was even higher in Beijing, where more than 80% of residents were opposed to wildlife consumption.

In comparison, about 42% of total respondents were against the practice during the previous survey in 2004.

Since the coronavirus epidemic, there has been vocal criticism of the trade in exotic animals and calls for a crackdown. A group of 19 academics from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and leading universities even jointly issued a public statement calling for an end to the trade, saying it should be treated as a “public safety issue.”

“The vast majority of people within China react to the abuse of wildlife in the way people in other countries do — with anger and revulsion,” said Aron White, wildlife campaigner at the Environmental Investigation Agency.

“I think we should listen to those voices that are calling for change and support those voices.”

Traditional medicine loophole

A significant barrier to a total ban on the wildlife trade is the use of exotic animals in traditional Chinese medicine.

Beijing has been strongly promoting the use of traditional Chinese medicine under President Xi Jinping and the industry is now worth an estimated $130 billion.

As recently as October 2019, state-run media China Daily reported Xi as saying that “traditional medicine is a treasure of Chinese civilization embodying the wisdom of the nation and its people.”

Many species that are eaten as food in parts of China are also used in the country’s traditional medicine.

The new ban makes an exception made for wild animals used in traditional Chinese medicine. According to the ruling, the use of wildlife is not illegal for this, but now must be “strictly monitored.” The announcement doesn’t make it clear, however, how this monitoring will occur or what the penalties are for inadequate protection of wild animals, leaving the door open to abuse.

A 2014 study by the Beijing Normal University and the China Wildlife Conservation Association found that while deer is eaten as a meat, the animal’s penis and blood are also used in medicine. Both bears and snakes are used for both food and medicine.

Wildlife campaigner Aron White said that under the new restrictions there was a risk of wildlife being sold or bred for medicine, but then trafficked for food. He said the Chinese government needed to avoid loopholes by extending the ban to all vulnerable wildlife, regardless of use.

“(Currently), the law bans the eating of pangolins but doesn’t ban the use of their scales in traditional Chinese medicine,” he said. “The impact of that is that overall the consumers are receiving mixed messages.”

The line between which animals are used for meat and which are used for medicine is also already very fine, because often people eat animals for perceived health benefits.

In a study published in International Health in February, US and Chinese researchers surveyed attitudes among rural citizens in China’s southern provinces to eating wild animals.

One 40-year-old peasant farmer in Guangdong says eating bats can prevent cancer. Another man says they can improve your vitality.

“‘I hurt my waist very seriously, it was painful, and I could not bear the air conditioner. One day, one of my friends made some snake soup and I had three bowls of it, and my waist obviously became better. Otherwise, I could not sit here for such a long time with you,” a 67-year-old Guangdong farmer told interviewers in the study.

Changing the culture

China’s rubber-stamp legislature, the National People’s Congress, will meet later this year to officially alter the Wildlife Protection Law. A spokesman for the body’s Standing Committee said the current ban is just a temporary measure until the new wording in the law can be drafted and approved.

Hong Kong virologist Leo Poon said the government has a big decision to make on whether it officially ends the trade in wild animals in China or simply tries to find safer options.

“If this is part of Chinese culture, they still want to consume a particular exotic animal, then the country can decide to keep this culture, that’s okay,” he said.

“(But) then they have to come up with another policy — how can we provide clean meat from that exotic animal to the public? Should it be domesticated? Should we do more checking or inspection? Implement some biosecurity measures?” he said.

An outright ban could raise just as many questions and issues. Ecohealth Alliance president Peter Daszak said if the trade was quickly made illegal, it would push it out of wet markets in the cities, creating black markets in rural communities where it is easier to hide the animals from the authorities.

Driven underground, the illegal trade of wild animals for consumption and medicine could become even more dangerous.

“Then we’ll see (virus) outbreaks begin not in markets this time, but in rural communities,” Daszak said. “(And) people won’t talk to authorities because it is actually illegal.”

Poon said the final effectiveness of the ban may depend on the government’s willpower to enforce the law. “Culture cannot be changed overnight, it takes time,” he said.

Original source: https://www.cnn.com

by Noah's Ark | Mar 26, 2020 | Animals, Conservation, Global |

As the Covid-19 pandemic spreads its tentacles across all continents except Antarctica, scientists in China and the US are racing to pin down its biological origins. Mounting findings across the globe highlight the world’s most trafficked mammal as the likely pandemic carrier.

A new paper by four Chinese researchers says the acute pneumonia that has killed almost 20,000 people worldwide (so far) almost undoubtedly recombined in pangolins before eventually jumping to humans.

Suggesting firm transmission links from bats to humans via pangolins, the research was released last week on bioRxiv (pronounced “bio archive”), a web discussion forum for unpublished preprints in the life sciences. This service is a widely used industry gold standard that allows the scientific community to immediately see and comment on findings before these are submitted for the rigorous and often lengthy peer-review process.

SARS-CoV-2, the single-strand RNA virus that causes Covid-19, is a likely recombinant between bat and pangolin coronaviruses, and pangolins are “the most possible intermediate reservoir”, the joint research team has found. Together they represent Hainan University, Fujian Normal University, Central South University and Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology.

Coronaviruses can infect a wide range of animals, including humans, and have caused major epidemics in the past.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome via civets caused a global outbreak in 2003, followed by Middle East Respiratory Syndrome via camels in 2012. Each is a coronavirus transmitted through intermediate mammal hosts with original links to bats.

Likely entering people through meat consumption, these coronaviruses transformed their hosts into brand-new vectors and were then spread by human contact.

Ha! Bats! Or is it?

To determine the mammal linkages to SARS-CoV-2 — the seventh species of coronavirus to infect humans — researchers Jiao-Mei Huang, Syed Sajid Jan, Xiaobin Wei, Yi Wan and Songying Ouyang analysed genomes from various potential hosts.

The team’s initial results are consistent with an escalating body of recent evidence exposing bats as the original “reservoir” source of the virus, but stress that pangolins appear to reflect a slightly higher resonance in some key aspects.

Coming out on top for whole-genome similarity, a bat coronavirus genome is 96% similar to SARS-CoV-2, while pangolin coronavirus shows a 90% similarity, the team points out.

In genetic terms, this difference is not insignificant. So let’s, for a second, pretend these data points are our only genetic clues to what sort of animals the pandemic strain may have hijacked before infecting humans.

At such a crime scene, we would be forgiven for punching the air and exclaiming, “Ha! It’s bats!”

But the Chinese virology detectives wanted just that extra bit of certainty, and knew the value of taking a high-resolution look at the “S-protein” cauliflower stalks peppered across the coronavirus’s ball-like surface.

This is where we might get really suspicious of bats, because the S-protein is crucial for viral infection and, in bats, it is up to 97.43% similar to the S-protein observed in SARS-CoV-2, the paper found. (We’re not saying ‘S’ means suspicious at all — Ed.)

That is right. A bat’s whole coronavirus genome is a 96% match to the latest human coronavirus genome. Plus, bat coronavirus has a seriously suspicious S-protein that seems to be an even higher match to its human equivalent. This suggests the SARS-CoV-2 spillover event to humans happened via bats.

However, our virology sleuths were not content to leave it there and rush into the court of academia, waving nothing but a body of batty evidence. They would be crummy RNA investigators if they did.

For it is in a terminus of the S-protein cauliflower stalks that the Chinese team probed deeper — that’s because most coronaviruses hide some of their most lethal arsenal right here, in the “receptor-binding domain”, or “RBD”, and its associated amino acid residues.

Think of the RBD and its amino acid accomplices as Trojan soldiers whose most desirous existential mission is to infiltrate what they might, in the cross-examination dock, describe as a “Troy” cell*. For argument’s sake, that Troy cell is, potentially, your cells, or another mammal’s cells. But different RBDs like to hijack different cells — meaning they don’t have a universal entry code to unlock every safe.

To unlock the safe, they need to have evolved the correct amino acid entry code.

How, according to the Chinese paper, does the RBD entry code in bat coronavirus compare with the SARS-CoV-2 variety found in humans?

“Um, it’s only about 89.57% similar, advocate,” SARS-CoV-2 might quiver in its little viral boots if questioned about how it broke into Patient Zero’s Troy cell.

And how about a pangolin coronavirus? “At least 96%.”

That’s the humdinger. The RBD and its amino acids in pangolin coronavirus is more than 96% similar to its SARS-CoV-2 counterparts.

Pangolins as a ‘missing link’

This does not mean pangolins, also known as scaly anteaters, are the final link in the chain that mutated into SARS-CoV-2 and has upended the entire human world — especially since the pangolin coronavirus’s whole genome comparison does not seem to exceed 90%.

Instead, the Chinese paper said the complex dance between whole genome, S-protein, RBD and amino acids suggests bat and pangolin viruses at some point shared genetic material within the RBD and recombined to form the virus that became SARS-CoV-2.

Due to the high RBD/amino-acid correlation, the paper also suggested that the pangolin is the “most possible intermediate SARS-CoV-2 reservoir, which may have given rise to cross-species transmission to humans”.

Following “mutations in coding regions of 125 SARS-CoV-2 genomes”, the researchers also attempted to track the virus’s evolution.

“Another important outcome of our analysis is the genetic mutations and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 as it spread globally. These findings are very significant for controlling the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” they proposed.

‘Identical to that of a pangolin coronavirus’

The Chinese researchers’ work strongly supports earlier preliminary findings by a US team at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas.

In February, Daily Maverick was the first publication globally to report that the US team had homed in on the critically endangered Malayan pangolin (Manis javanica) as a likely intermediate reservoir of SARS-CoV-2.

Bioinformatics researcher Matthew Wong had found that the distinctive RBD docking mechanism in SARS-CoV-2 was “identical to that of a pangolin coronavirus”, his Baylor College lab supervisor, Professor Joseph Petrosino, told Daily Maverick.

A pangolin virus and bat virus may have found themselves in the same animal, he said, leading to what he described as a “devastating recombination event, creating the pandemic strain. This may have happened in the wild, or where these animals were brought together in unnaturally close proximity.”

Now being prepared for peer review, their analysis is based on a 2019 study of 21 Malayan pangolins — an especially popular species among traffickers — at a wildlife rescue centre in China’s Guangdong province.

The original research on the Guangdong pangolins was the first report on pangolins’ viral diversity.

Nonetheless, Petrosino was scientifically cautious — pangolins aren’t necessarily the closest link to humans.

“We do not know the order, or even where, the recombination events took place — whether it was in a bat, or a pangolin, or even whether there were other animals involved in the process that have yet to be discovered,” he said.

In January authorities had isolated SARS-CoV-2 in environmental samples from an unsanitary wildlife market in the Chinese city of Wuhan, but these results did not mean there were pangolins at the market.

For their part, there was only one thing Petrosino and his colleagues could say for certain.

“A virus known to exist in bats and a virus found in a pangolin-virus sample appeared to have recombined to form [SARS-CoV-2]. But, some viruses can be transmitted between mammals relatively easily, so there’s no way to tell whether there is another animal where these two viruses perhaps co-existed. More surveillance is necessary.”

Research gathers global momentum

Announced on the same day that Daily Maverick reported on the Baylor College findings, additional preliminary findings by a team of 26 researchers from South China Agricultural University had also found correlations between pangolin and SARS-CoV-2 RBDs.

This university’s detailed findings, posted on the bioRxiv forum on 20 February, made global headlines but have been challenged by some scientists.

However, since Baylor College emerged as the first academic team to share their seminal comparison study on bioRxiv on 13 February, at least 11 additional independent Australian, Chinese and US studies exploring pangolins as possible intermediate carriers have been made public on this very forum.

At the time of writing, the Baylor College and South China Agricultural University preprints had soared to the 99th percentile of some 15 million research outputs ever monitored by the forum’s global “attention tracker”.

And the other preprints — none of which were peer-reviewed when posted to the forum — generally agree:

- Pangolin coronaviruses appear to be genetic kin of both SARS-CoV-2 and bat coronaviruses.

- Since pangolin RBDs seem most closely related to SARS-CoV-2, this suggests not only a recombination event between pangolins and bats at some point during the virus’s evolution, but that pangolins may be more infectious to humans than bats.

- Bats still appear to be the original reservoir host, but pangolins are the likeliest intermediate vector yet.

In their conclusions, all preprints urged further research.

“Indeed, the discovery of viruses in pangolins suggests there is a wide diversity of coronaviruses still to be sampled in wildlife, some of which may be directly involved in the emergence of [SARS-CoV-2],” said researchers in yet another bioRxiv study, this time by Chinese and Australian institutions.

The preprints made other pointed recommendations, such as introducing urgent mechanisms to end wildlife trade; removing pangolins from wet markets to halt zoonotic transfer; and extensively monitoring pangolin virology.

“Large surveillance of coronaviruses in pangolins,” recommended another study by Chinese and US institutions, “could improve our understanding of the spectrum of coronaviruses in pangolins.”

Big academia weigh in: it is NOT biological warfare

Wild and unsubstantiated conspiracy rumours have been floated about the genesis of the virus, including that it escaped from a Wuhan laboratory — but a paper published in Nature Medicine last week thoroughly debunked this.

As a peer-reviewed paper in one of the world’s most respected journals, it also added authority to the hypothesis of pangolins as a likely intermediate vector.

The paper, by Australian, UK and US institutions, attributed the virus origins to zoonotic transfer from an animal, possibly arising in the Rhinolophus affinis bat and then spilling over into a pangolin.

“It is possible that a progenitor of SARS-CoV-2 jumped into humans,” they report, “acquiring the genomic features described above through adaptation during undetected human-to-human transmission. Once acquired, these adaptations would enable the pandemic to take off.”

Will pangolins come and save us?

“In the midst of the global Covid-19 public-health emergency,” the Nature study offered, “it is reasonable to wonder why the origins of the pandemic matter.”

But they do matter.

“The trade in and consumption of wild animals is not only an animal welfare issue, it’s a human rights travesty as attested by a pandemic that has brought the world to its knees,” said Audrey Delsink, wildlife director at Humane Society International in Africa.

“Detailed understanding of how an animal virus jumped species boundaries to infect humans so productively will help in the prevention of future zoonotic events,” the Nature study concluded. “If SARS-CoV-2 pre-adapted in another animal species, then there is the risk of future re-emergence events.”

Peter Knights of international conservation organisation WildAid warned that pangolins, among the world’s most endangered and trafficked mammals, are highly pathogenic.

“Whether or not Covid-19 is found to have been transmitted through pangolins, it certainly could have been — and, if current levels of illegal trade continue, they could be a vector for another new disease. Pangolins have high pathogen loads and carry parasites, like ticks. They are also massively stressed, malnourished and dehydrated when in trade,” said Knights, who in recent years has had success working with the Chinese government to reduce the consumption of shark-fin soup by a reported 80%.

Scientists may have mapped only a fraction of wildlife viruses, which have co-evolved in a staggering variety of insects and animals — not just pangolins and bats.

The majority of known emerging infectious diseases — especially viruses — are of animal origin, said a Royal Society paper by scientists from Cambridge University, London’s Zoological Society and EcoHealth Alliance. The proportion of those emerging from wildlife hosts, they noted, increased substantially over the 20th century’s last four decades.

This underlined the urgency of redrawing the architecture of medical science to join holistic dots between public health, non-human life, the hidden costs of economic development and degraded ecosystems, which biodiversity scientists warn are a hotbed for emerging infectious diseases. Our relatively poor understanding of the extent of disease in wildlife shows that the virology-research vessel may have hit only the tip of the iceberg and, to conservationists like Knights, this makes the trajectory of emergency response obvious, not just in China, but in other key regions of the human planet.

“All governments with bushmeat and wildlife consumption primarily in South East Asia and West and Central Africa should review their legislation, penalties, enforcement efforts and public awareness of the risks at this time. All live wildlife markets should be closed around the world,” he urged.

It seems African governments may be following suit. Last week the Nyasa Times reported that Malawi would ban the sale and consumption of bushmeat. A mass Covid-19 “sensitisation” campaign would follow.

Knights cautioned: “It’s obvious that some species should not be allowed to be consumed at all, while there may be some ‘safe’ species: like rabbits, quail, some deer and antelope and grasscutters.

“As we add species of conservation concern or health risk, the banned list gets longer and longer. Instead, we should be looking at a short ‘clean’ list of animals that can be legally consumed and enforced, and the public [will] know that everything else is off limits.” DM

* “Troy cell” is used metaphorically to illustrate an example. It’s not meant to be used or interpreted as a scientific term.

Original source: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za