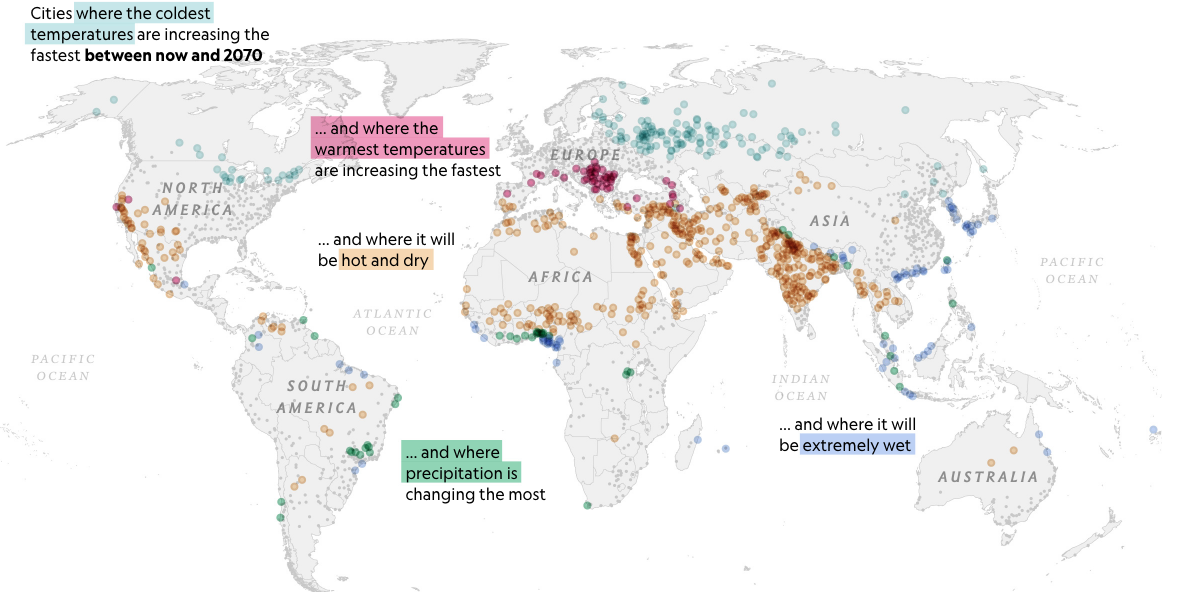

The whole planet will feel climate change’s impacts over coming decades. But some cities will see more dramatic changes in temperatureor precipitation than others.

More and more of us live in urban areas. Today, some 55 percent of the world lives in cities, and a quarter of all humans live in the 2,500 most populous cities. That percentage is expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades. By 2050, as the global population swells and urbanizes, about 70 percent of people will live in metropolises.

Earth’s climate, meantime, will continue to change in response to ever-rising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. Further warming will induce dramatic changes in nearly every corner of the planet. Some of those effects are already playing out.

Many of the impacts of future warming will be felt by the growing population of city dwellers. Cities concentrate people, infrastructure, activity, and many other resources into tight spaces, which means they’re particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Hotter temperatures put extra stress on human bodies, asphalt-covered roads, and more; more intense droughts can tax water systems; more intense rainfall can flood cities’ drains.

National Geographic partnered with University of Maryland climate scientist Matt Fitzpatrick to look at how temperature and precipitation patterns in many of the major urban areas of the world could change by 2070 if significant efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions are not made quickly—the “RCP 8.5” scenario.

The conclusions are clear: Just about everywhere in the world will experience shifts in seasons, hotter highs, and more extreme wet and dry periods. Some urban areas will feel more intense changes than others. But the alarming predictions are not set in stone. Today’s decisions can still influence tomorrow’s experience.

Warmer warms

Cities are affected more than rural areas by increasing air temperatures because they’re already hotter. Concrete, steel, wood, and other infrastructure materials trap more heat than a natural landscape does: the so-called urban heat island effect.

Unchecked climate change will drive temperatures up dramatically in every one of the 2,500 locations studied. During summer, the highest high temperatures are projected to increase by an average of 8 degrees Fahrenheit by 2070. In some places, the heat will be even more extreme. Summer temperatures in Urmia, Iran, for instance, will experience a 15-degree uptick, with average hot temperatures hovering at 98 degrees Fahrenheit.

Currently, only 9 percent of the cities studied have summer maximum temperatures that exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit, but that number will more than double by 2070. Among those future cities experiencing intense heat will be Grand Junction, Colorado, where today’s summer maximum temperatures of 90 degrees are projected to hit 100 degrees in 2070.

Cold seasons get less cold

The hot parts of the world are getting hotter, but some of the more dramatic changes are already happening—and will continue to unfold—in the places that are supposed to be cold. In general, the cold seasons in these places are warming up more quickly than warmer places’ warm seasons. The Arctic, for example, is heating up roughly twice as fast as the world on average, and its winters are taking the brunt of that warming.

Cities in the Far North will continue to feel their winters warm, if no major climate-curbing actions are taken soon. Among the 2,500 cities studied, the average minimum temperatures during winter are expected to increase 7.3 degrees Fahrenheit between now and 2070.

That’s enough to push some places over a dangerous tipping point from freezing into not freezing; snow to rain; ice to liquid; permafrost to sloppy, carbon-releasing mud.

The effects could be devastating. Snow that falls in the mountains of the western United States, for example, acts as a “water tower,” melting slowly through the spring and summer, providing water to areas downstream. If that snow falls as rain, the threat of later-season drought increases. Many agricultural crops, like almonds, wine grapes, and peaches, require a chill to produce fruit. Freezing temperatures also kill off pests, such as mosquitoes, ticks, and beetles, so warming winters could amplify the spread of vector-borne diseases and facilitate the earlier emergence of adult mosquitoes.

Cities outside the Far North will also see their cold seasons change. Today, 36 percent of the cities analyzed experience minimum winter temperatures below freezing. By 2070, 62 percent of the cities analyzed will no longer have below freezing winters.

What’s happening to the rain?

Another likely outcome of climate change is that the subtropics—regions just north or south of the tropics, such as northern Mexico or the Argentinean Pampas—will get drier. In general, higher latitudes are predicted to see more total precipitation, particularly rainfall, as the Earth warms. Exactly how those changes will play out seasonally is harder to pin down, though.

All in all, we should expect “more intense but less frequent precipitation,” says Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA, with longer dry stretches between rainfall events.

Some cities that will experience drying will be better equipped to handle it than others, Fitzpatrick says. Places that already get abundant rainfall will be less strapped by a 20 percent decrease than somewhere that’s already really dry.

“A 20 percent decrease in an area that already has marginal rainfall,” he says, “very easily could transition it to a place with significant water issues.”

For every one degree Celsius the air heats up, the atmosphere holds 7 percent more water vapor. That means that by the end of the century the atmosphere will be able to hold 27 percent more water vapor than it does today. Adding that much more precipitation into the world’s water cycle will create more intense rainfall, particularly escalating the risk of flooding.

Much of the change is likely to occur during the cooler months of the year: 812 cities will have almost no precipitation, but many others will have extreme precipitation. And while many of the most extreme cities will get drier,11 cities across Nigeria, Rwanda, and Cameroon will also experience significantly more precipitation in 2070.

Original source: https://www.nationalgeographic.com