by Noah's Ark | Apr 9, 2020 | Climate Action, Climate Change, Global |

In the past few weeks, we have seen changes in society that would have been unthinkable just last year. The coronavirus pandemic has trapped us indoors, deprived us of our normal routines, and unleashed a global economic catastrophe not seen since the second world war. This crisis has reshaped how we think about ourselves, rapidly transformed our values, and caused a surreal shift in time and space. Suddenly, we are under siege from the stark reality of our immediate survival.

Even though our instincts and political leaders might be saying otherwise, it is more important than ever in this emergency to take the long view. If there was ever a moment to think about the future, it’s now.

The coronavirus has plunged the world headfirst into an era of unity, solidarity, and rapid societal change that looks like a compressed version of what climate scientists have been warning us about for decades. We are part of a living ecosystem, and if we push it too far, it will break.

Looking around us, we can clearly see some of the cracks in society. We now know the status quo has failed. These sudden transformations are a collective trauma, Read about the overlap between climate grief and the coronavirus, by Mary Annaïse Heglar.argues climate justice writer Mary Annaïse Heglar. We are in mourning for a familiar world that has suddenly vanished. The old world is not coming back. There is a tangible sense of grief and loss. It’s a moment of triage for the entire planet.

Our twofold task There are striking parallels between this short-term fight against Covid-19 and the long-term fight for a stable climate. Most importantly: we know what the solutions are, we know that the solutions will work, and we know they must take place on an enormous scale. Our actions from this point will require a more compassionate, caring, equal, and just global society – if for any other reason than sheer survival.

Our task in this moment is twofold: we have to urgently prevent social and economic collapse and build a new world at the same time. If we trust scientists, on climate and coronavirus, both of those are equally important.

What we do now will not only alter the course of this pandemic; it will also shape large parts of our collective futures. Restoring the status quo shouldn’t be our goal. Decarbonising the economy and strengthening social safety nets is the best way to ensure a more stable and prosperous society going forward.

The Jurassic Park problem

The hardest truth is realising that this crisis is going to get a lot worse before it gets better. Among friends, I’m referring to this as the Jurassic Park problem. In the movie, one of the main characters tries to switch off the power to an amusement park filled with dinosaurs, Watch a clip of the scene from Jurassic Park (1993).a system that was never meant to be powered down. When they switch it back on, chaos ensues, the dinosaurs escape, and we realise that when fragile systems break, they can break quickly.

With a quarter of the world under lockdown, we are foolish to think we can bring our entire economy back online as it was with no problems. We have to create a new system.

Governments have already pledged trillions of dollars in emergency funding to battle the coronavirus pandemic, and those plans are quickly becoming reality. In India, currently home to the largest and strictest lockdown in the world, leaders have announced a $22bn rescue plan, which amounts to less than $20 for each of its 1.3 billion citizens. In the US, a $2tn stimulus package has been approved, including billions for companies like Boeing, one of the world’s largest defence contractors, which has spent years funnelling taxpayer money to prop up its own share price. Almost immediately afterwards, US lawmakers have gotten to work on plans to free up an additional $2tn of infrastructure spending.

In the EU, Germany has declared emergency powers to lift its national debt limit to fund a bailout for corporations. The tourism-dependent Caribbean has spent decades cultivating an economy catering to the whims of rich travelers. The cruise line industry is asking for bailout money, but how much of that will make its way to workers in the Bahamas or Jamaica? Italy and Spain have so far seen the worst of the pandemic and are also highly dependent on tourism revenue. With global air travel all but shut down, it’s an open question how their economies will fare. If either country collapses, it could send a cascade of financial pain throughout the world.

For the most part, all this money isn’t just a stimulus or a bailout – it’s life support for the status quo.

Three steps to recover from this crisis Ending the Covid-19 pandemic isn’t just about saving lives and getting back to normal. It’s about rebuilding our social safety nets. Ending the climate emergency is not just about reducing emissions. It’s about treating each other better.

What would that collective response look like?

In the US, the pandemic has refocused the conversation on what kind of social safety nets our current system has been missing, and what kind of system we might be able to build to replace the (failed) privatised-capitalist one that treats workers as machines. Thinking of healthcare, housing, jobs, and a stable environment as universal rights – and the main organising principles of society, instead of profit-making – is a much more stable way of building an economy.

We cannot be satisfied with coronavirus recovery plans that only allow us to survive. We must also demand plans that will help us thrive. We must be forward-thinking, not reactionary.

Here are three important steps we could take to inject long-term thinking into our short-term crisis recovery:

Nationalise the fossil fuel and airline industry.

The collapse in oil prices has created a remarkable opportunity to end the climate emergency. The fossil fuel industry has spent decades sabotaging the planet’s life support system and building a fragile global economic system that’s now at risk of collapse. Governments should purchase majority shares in the largest-polluting industries, Read climate journalist Kate Aronoff’s proposal for nationalising the fossil fuel industry.such as oil companies, airlines, and cruise lines, and repurpose them for a zero-carbon future. As a majority shareholder, we – the taxpayers who would own these companies – could force them to become non-profit entities and rapidly advance their progress investing in renewable energy, electric airplanes, passenger rail, and other forms of low-carbon travel.

Even while fending off coronavirus, Italy has already nationalised their major airline, Alitalia. With oil prices plunging, a controlling stake in the world’s five largest oil companies – Shell, BP, ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Total – could be purchased for about $400bn right now, compared to about twice that at the start of 2020. If that happened, we could wind down their operations in line with science-based climate targets and justice for their workers.

Public works projects on an enormous scope and scale

Dollar-for-dollar, investment in large building projects is one of the best stimulus payoffs, but we need to cast a wide net and make sure everyone has a chance to participate in the new economy. With long-term interest rates less than 1% right now (or even negative in some countries), there’s virtually an unlimited amount of money available for public works projects that could help create the carbon-free economy we all need.

A group of academics has outlined dozens of ideas for how this money could be spent, including retrofitting every building, no-interest loans for cities to build new sewer systems, and funding farmers to practise regenerative agriculture. The ideas have already been endorsed by hundreds of experts and have broad public support in the US. The main idea in their proposals is that this new infrastructure money absolutely must not be spent on building roads and airports that will reinforce the failed fossil fuel economy, but instead on building the kind of infrastructure that will power the world for the rest of the century.

And with unemployment rates surging, this is a perfect time to put people to work in large-scale infrastructure projects. Investing in a green stimulus plan would be a source of millions of new jobs over the next decade, for less than half of the cost of this week’s US bailout plan.

Strengthen social safety nets

Last year, it was unthinkable that the US would institute a universal basic income anytime soon. Now, it’s on the verge of becoming a reality.

After Andrew Yang, a presidential contender, brought the idea into the mainstream in the US, many politicians, including Donald Trump, have been considering the idea.

The next step will be declaring other necessities such as healthcare, housing, and jobs as a human right. These are core parts of the Green New Deal framework for climate policy, and the coronavirus crisis has proven they’re not out of reach in the near term.

The establishment of a society that cares about supporting life instead of economic growth Read Jason Hickel’s essay, ‘Outgrowing growth’.will be the key to solving this crisis the right way. The Great Depression led to the New Deal. If we do this right, we’ll create a world that’s more resilient to future disasters because we have distributed and decentralised our power supply and tackled the climate emergency. Read my speculative preview of the 2020s.

Reluctance to these ideas only exists because they threaten the power of the status quo. But in the past few days, we’ve shut down a huge portion of society out of solidarity for each other to save each other’s lives. What more good are we capable of?

Original source: https://thecorrespondent.com/

by Noah's Ark | Apr 6, 2020 | Climate Change, Global, Natural World |

The world was a different place back then. During the middle of the Cretaceous period (145 million to 65 million years ago), dinosaurs roamed Earth and sea levels were 558 feet (170 meters) higher than they are today. Sea-surface temperatures in the tropics were as hot as 95 degrees Fahrenheit (35 degrees Celsius).

This scorching climate allowed a rainforest — similar to those seen in New Zealand today — to take root in Antarctica, the researchers said.

The rainforest’s remains were discovered under the ice in a sediment core that a team of international researchers collected from a seabed near Pine Island Glacier in West Antarctica in 2017.

As soon as the team saw the core, they knew they had something unusual. The layer that had formed about 90 million years ago was a different color. “It clearly differed from the layers above it,” study lead researcher Johann Klages, a geologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany, said in a statement.

Back at the lab, the team put the core into a CT (computed tomography) scanner. The resulting digital image showed a dense network of roots throughout the entire soil layer. The dirt also revealed ancient pollen, spores and the remnants of flowering plants from the Cretaceous period.

By analyzing the pollen and spores, study co-researcher Ulrich Salzmann, a paleoecologist at Northumbria University in England, was able to reconstruct West Antarctica’s 90 million-year-old vegetation and climate. “The numerous plant remains indicate that the coast of West Antarctica was, back then, a dense temperate, swampy forest, similar to the forests found in New Zealand today,” Salzmann said in the statement.

The sediment core revealed that during the mid-Cretaceous, West Antarctica had a mild climate, with an annual mean air temperature of about 54 F (12 C), similar to that of Seattle. Summer temperatures were warmer, with an average of 66 F (19 C). In rivers and swamps, the water would have reached up to 68 F (20 C).

In addition, the rainfall back then was comparable to the rainfall of Wales, England, today, the researchers found.

These temperatures are impressively warm, given that Antarctica had a four-month polar night, meaning that a third of every year had no life-giving sunlight. However, the world was warmer back then, in part, because the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere was high — even higher than previously thought, according to the analysis of the sediment core, the researchers said.

“Before our study, the general assumption was that the global carbon dioxide concentration in the Cretaceous was roughly 1,000 ppm [parts per million],” study co-researcher Gerrit Lohmann, a climate modeler at Alfred Wegener Institute, said in the statement. “But in our model-based experiments, it took concentration levels of 1,120 to 1,680 ppm to reach the average temperatures back then in the Antarctic.”

These findings show how potent greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide can cause temperatures to skyrocket, so much so that today’s freezing West Antarctica once hosted a rainforest. Moreover, it shows how important the cooling effects of today’s ice sheets are, the researchers said.

Original source: https://www.livescience.com

by Noah's Ark | Mar 30, 2020 | Animals, Conservation, Global |

A strict ban on the consumption and farming of wild animals is being rolled out across China in the wake of the deadly coronavirus epidemic, which is believed to have started at a wildlife market in Wuhan.

Although it is unclear which animal transferred the virus to humans — bat, snake and pangolin have all been suggested — China has acknowledged it needs to bring its lucrative wildlife industry under control if it is to prevent another outbreak.

In late February, it slapped a temporary ban on all farming and consumption of “terrestrial wildlife of important ecological, scientific and social value,” which is expected to be signed into law later this year.

But ending the trade will be hard. The cultural roots of China’s use of wild animals run deep, not just for food but also for traditional medicine, clothing, ornaments and even pets.

This isn’t the first time Chinese officials have tried to contain the trade. In 2003, civets — mongoose-type creatures — were banned and culled in large numbers after it was discovered they likely transferred the SARS virus to humans. The selling of snakes was also briefly banned in Guangzhou after the SARS outbreak.

But today dishes using the animals are still eaten in parts of China.

Public health experts say the ban is an important first step, but are calling on Beijing to seize this crucial opportunity to close loopholes — such as the use of wild animals in traditional Chinese medicine — and begin to change cultural attitudes in China around consuming wildlife.

Markets with exotic animals

The Wuhan seafood market at the centre of the novel coronavirus outbreak was selling a lot more than fish.

Snakes, raccoon dogs, porcupines and deer were just some of the species crammed inside cages, side by side with shoppers and store owners, according to footage obtained by CNN. Some animals were filmed being slaughtered in the market in front of customers. CNN hasn’t been able to independently verify the footage, which was posted to Weibo by a concerned citizen, and has since been deleted by government censors.

It is somewhere in this mass of wildlife that scientists believe the novel coronavirus likely first spread to humans. The disease has now infected more than 94,000 people and killed more than 3,200 around the world.

The Wuhan market was not unusual. Across mainland China, hundreds of similar markets offer a wide range of exotic animals for a range of purposes.

The danger of an outbreak comes when many exotic animals from different environments are kept in close proximity.

“These animals have their own viruses,” said Hong Kong University virologist professor Leo Poon. “These viruses can jump from one species to another species, then that species may become an amplifier, which increases the amount of virus in the wet market substantially.”

When a large number of people visit markets selling these animals each day, Poon said the risk of the virus jumping to humans rises sharply.

Poon was one of the first scientists to decode the SARS coronavirus during the epidemic in 2003. It was linked to civet cats kept for food in a Guangzhou market, but Poon said researchers still wonder whether SARS was transmitted to the cats from another species.

“(Farmed civet cats) didn’t have the virus, suggesting they acquired it in the markets from another animal,” he said.

Strength and status

Annie Huang, a 24-year-old college student from southern Guangxi province, said she and her family regularly visit restaurants that serve wild animals.

She said eating wildlife, such as boar and peacock, is considered good for your health, because diners also absorb the animals’ physical strength and resilience.

Exotic animals can also be an important status symbol. “Wild animals are expensive. If you treat somebody with wild animals, it will be considered that you’re paying tribute,” she said. A single peacock can cost as much as 800 yuan ($144).

Huang asked to use a pseudonym when speaking about the newly-illegal trade because of her views on eating wild animals.

She said she doubted the ban would be effective in the long run. “The trade might lay low for a few months … but after a while, probably in a few months, people would very possibly come back again,” she said

Beijing hasn’t released a full list of the wild animals included in the ban, but the current Wildlife Protection Law gives some clues as to what could be banned. That law classifies wolves, civet cats and partridges as wildlife, and states that authorities “should take measures” to protect them, with little information on specific restrictions.

The new ban makes exemptions for “livestock,” and in the wake of the ruling animals including pigeons and rabbits are being reclassified as livestock to allow their trade to continue.

Billion-dollar industry

Attempts to control the spread of diseases are also hindered by the fact that the industry for exotic animals in China, especially wild ones, is enormous.

A government-sponsored report in 2017 by the Chinese Academy of Engineering found the country’s wildlife trade was worth more than $73 billion and employed more than one million people.

Since the virus hit in December, almost 20,000 wildlife farms across seven Chinese provinces have been shut down or put under quarantine, including breeders specializing in peacocks, foxes, deer and turtles, according to local government press releases.

It isn’t clear what effect the ban might have on the industry’s future — but there are signs China’s population may have already been turning away from eating wild animals even before the epidemic.

A study by Beijing Normal University and the China Wildlife Conservation Association in 2012, found that in China’s major cities, a third of people had used wild animals in their lifetime for food, medicine or clothing — only slightly less than in their previous survey in 2004.

However, the researchers also found that just over 52% of total respondents agreed that wildlife should not be consumed. It was even higher in Beijing, where more than 80% of residents were opposed to wildlife consumption.

In comparison, about 42% of total respondents were against the practice during the previous survey in 2004.

Since the coronavirus epidemic, there has been vocal criticism of the trade in exotic animals and calls for a crackdown. A group of 19 academics from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and leading universities even jointly issued a public statement calling for an end to the trade, saying it should be treated as a “public safety issue.”

“The vast majority of people within China react to the abuse of wildlife in the way people in other countries do — with anger and revulsion,” said Aron White, wildlife campaigner at the Environmental Investigation Agency.

“I think we should listen to those voices that are calling for change and support those voices.”

Traditional medicine loophole

A significant barrier to a total ban on the wildlife trade is the use of exotic animals in traditional Chinese medicine.

Beijing has been strongly promoting the use of traditional Chinese medicine under President Xi Jinping and the industry is now worth an estimated $130 billion.

As recently as October 2019, state-run media China Daily reported Xi as saying that “traditional medicine is a treasure of Chinese civilization embodying the wisdom of the nation and its people.”

Many species that are eaten as food in parts of China are also used in the country’s traditional medicine.

The new ban makes an exception made for wild animals used in traditional Chinese medicine. According to the ruling, the use of wildlife is not illegal for this, but now must be “strictly monitored.” The announcement doesn’t make it clear, however, how this monitoring will occur or what the penalties are for inadequate protection of wild animals, leaving the door open to abuse.

A 2014 study by the Beijing Normal University and the China Wildlife Conservation Association found that while deer is eaten as a meat, the animal’s penis and blood are also used in medicine. Both bears and snakes are used for both food and medicine.

Wildlife campaigner Aron White said that under the new restrictions there was a risk of wildlife being sold or bred for medicine, but then trafficked for food. He said the Chinese government needed to avoid loopholes by extending the ban to all vulnerable wildlife, regardless of use.

“(Currently), the law bans the eating of pangolins but doesn’t ban the use of their scales in traditional Chinese medicine,” he said. “The impact of that is that overall the consumers are receiving mixed messages.”

The line between which animals are used for meat and which are used for medicine is also already very fine, because often people eat animals for perceived health benefits.

In a study published in International Health in February, US and Chinese researchers surveyed attitudes among rural citizens in China’s southern provinces to eating wild animals.

One 40-year-old peasant farmer in Guangdong says eating bats can prevent cancer. Another man says they can improve your vitality.

“‘I hurt my waist very seriously, it was painful, and I could not bear the air conditioner. One day, one of my friends made some snake soup and I had three bowls of it, and my waist obviously became better. Otherwise, I could not sit here for such a long time with you,” a 67-year-old Guangdong farmer told interviewers in the study.

Changing the culture

China’s rubber-stamp legislature, the National People’s Congress, will meet later this year to officially alter the Wildlife Protection Law. A spokesman for the body’s Standing Committee said the current ban is just a temporary measure until the new wording in the law can be drafted and approved.

Hong Kong virologist Leo Poon said the government has a big decision to make on whether it officially ends the trade in wild animals in China or simply tries to find safer options.

“If this is part of Chinese culture, they still want to consume a particular exotic animal, then the country can decide to keep this culture, that’s okay,” he said.

“(But) then they have to come up with another policy — how can we provide clean meat from that exotic animal to the public? Should it be domesticated? Should we do more checking or inspection? Implement some biosecurity measures?” he said.

An outright ban could raise just as many questions and issues. Ecohealth Alliance president Peter Daszak said if the trade was quickly made illegal, it would push it out of wet markets in the cities, creating black markets in rural communities where it is easier to hide the animals from the authorities.

Driven underground, the illegal trade of wild animals for consumption and medicine could become even more dangerous.

“Then we’ll see (virus) outbreaks begin not in markets this time, but in rural communities,” Daszak said. “(And) people won’t talk to authorities because it is actually illegal.”

Poon said the final effectiveness of the ban may depend on the government’s willpower to enforce the law. “Culture cannot be changed overnight, it takes time,” he said.

Original source: https://www.cnn.com

by Noah's Ark | Mar 26, 2020 | Animals, Conservation, Global |

As the Covid-19 pandemic spreads its tentacles across all continents except Antarctica, scientists in China and the US are racing to pin down its biological origins. Mounting findings across the globe highlight the world’s most trafficked mammal as the likely pandemic carrier.

A new paper by four Chinese researchers says the acute pneumonia that has killed almost 20,000 people worldwide (so far) almost undoubtedly recombined in pangolins before eventually jumping to humans.

Suggesting firm transmission links from bats to humans via pangolins, the research was released last week on bioRxiv (pronounced “bio archive”), a web discussion forum for unpublished preprints in the life sciences. This service is a widely used industry gold standard that allows the scientific community to immediately see and comment on findings before these are submitted for the rigorous and often lengthy peer-review process.

SARS-CoV-2, the single-strand RNA virus that causes Covid-19, is a likely recombinant between bat and pangolin coronaviruses, and pangolins are “the most possible intermediate reservoir”, the joint research team has found. Together they represent Hainan University, Fujian Normal University, Central South University and Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology.

Coronaviruses can infect a wide range of animals, including humans, and have caused major epidemics in the past.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome via civets caused a global outbreak in 2003, followed by Middle East Respiratory Syndrome via camels in 2012. Each is a coronavirus transmitted through intermediate mammal hosts with original links to bats.

Likely entering people through meat consumption, these coronaviruses transformed their hosts into brand-new vectors and were then spread by human contact.

Ha! Bats! Or is it?

To determine the mammal linkages to SARS-CoV-2 — the seventh species of coronavirus to infect humans — researchers Jiao-Mei Huang, Syed Sajid Jan, Xiaobin Wei, Yi Wan and Songying Ouyang analysed genomes from various potential hosts.

The team’s initial results are consistent with an escalating body of recent evidence exposing bats as the original “reservoir” source of the virus, but stress that pangolins appear to reflect a slightly higher resonance in some key aspects.

Coming out on top for whole-genome similarity, a bat coronavirus genome is 96% similar to SARS-CoV-2, while pangolin coronavirus shows a 90% similarity, the team points out.

In genetic terms, this difference is not insignificant. So let’s, for a second, pretend these data points are our only genetic clues to what sort of animals the pandemic strain may have hijacked before infecting humans.

At such a crime scene, we would be forgiven for punching the air and exclaiming, “Ha! It’s bats!”

But the Chinese virology detectives wanted just that extra bit of certainty, and knew the value of taking a high-resolution look at the “S-protein” cauliflower stalks peppered across the coronavirus’s ball-like surface.

This is where we might get really suspicious of bats, because the S-protein is crucial for viral infection and, in bats, it is up to 97.43% similar to the S-protein observed in SARS-CoV-2, the paper found. (We’re not saying ‘S’ means suspicious at all — Ed.)

That is right. A bat’s whole coronavirus genome is a 96% match to the latest human coronavirus genome. Plus, bat coronavirus has a seriously suspicious S-protein that seems to be an even higher match to its human equivalent. This suggests the SARS-CoV-2 spillover event to humans happened via bats.

However, our virology sleuths were not content to leave it there and rush into the court of academia, waving nothing but a body of batty evidence. They would be crummy RNA investigators if they did.

For it is in a terminus of the S-protein cauliflower stalks that the Chinese team probed deeper — that’s because most coronaviruses hide some of their most lethal arsenal right here, in the “receptor-binding domain”, or “RBD”, and its associated amino acid residues.

Think of the RBD and its amino acid accomplices as Trojan soldiers whose most desirous existential mission is to infiltrate what they might, in the cross-examination dock, describe as a “Troy” cell*. For argument’s sake, that Troy cell is, potentially, your cells, or another mammal’s cells. But different RBDs like to hijack different cells — meaning they don’t have a universal entry code to unlock every safe.

To unlock the safe, they need to have evolved the correct amino acid entry code.

How, according to the Chinese paper, does the RBD entry code in bat coronavirus compare with the SARS-CoV-2 variety found in humans?

“Um, it’s only about 89.57% similar, advocate,” SARS-CoV-2 might quiver in its little viral boots if questioned about how it broke into Patient Zero’s Troy cell.

And how about a pangolin coronavirus? “At least 96%.”

That’s the humdinger. The RBD and its amino acids in pangolin coronavirus is more than 96% similar to its SARS-CoV-2 counterparts.

Pangolins as a ‘missing link’

This does not mean pangolins, also known as scaly anteaters, are the final link in the chain that mutated into SARS-CoV-2 and has upended the entire human world — especially since the pangolin coronavirus’s whole genome comparison does not seem to exceed 90%.

Instead, the Chinese paper said the complex dance between whole genome, S-protein, RBD and amino acids suggests bat and pangolin viruses at some point shared genetic material within the RBD and recombined to form the virus that became SARS-CoV-2.

Due to the high RBD/amino-acid correlation, the paper also suggested that the pangolin is the “most possible intermediate SARS-CoV-2 reservoir, which may have given rise to cross-species transmission to humans”.

Following “mutations in coding regions of 125 SARS-CoV-2 genomes”, the researchers also attempted to track the virus’s evolution.

“Another important outcome of our analysis is the genetic mutations and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 as it spread globally. These findings are very significant for controlling the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” they proposed.

‘Identical to that of a pangolin coronavirus’

The Chinese researchers’ work strongly supports earlier preliminary findings by a US team at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas.

In February, Daily Maverick was the first publication globally to report that the US team had homed in on the critically endangered Malayan pangolin (Manis javanica) as a likely intermediate reservoir of SARS-CoV-2.

Bioinformatics researcher Matthew Wong had found that the distinctive RBD docking mechanism in SARS-CoV-2 was “identical to that of a pangolin coronavirus”, his Baylor College lab supervisor, Professor Joseph Petrosino, told Daily Maverick.

A pangolin virus and bat virus may have found themselves in the same animal, he said, leading to what he described as a “devastating recombination event, creating the pandemic strain. This may have happened in the wild, or where these animals were brought together in unnaturally close proximity.”

Now being prepared for peer review, their analysis is based on a 2019 study of 21 Malayan pangolins — an especially popular species among traffickers — at a wildlife rescue centre in China’s Guangdong province.

The original research on the Guangdong pangolins was the first report on pangolins’ viral diversity.

Nonetheless, Petrosino was scientifically cautious — pangolins aren’t necessarily the closest link to humans.

“We do not know the order, or even where, the recombination events took place — whether it was in a bat, or a pangolin, or even whether there were other animals involved in the process that have yet to be discovered,” he said.

In January authorities had isolated SARS-CoV-2 in environmental samples from an unsanitary wildlife market in the Chinese city of Wuhan, but these results did not mean there were pangolins at the market.

For their part, there was only one thing Petrosino and his colleagues could say for certain.

“A virus known to exist in bats and a virus found in a pangolin-virus sample appeared to have recombined to form [SARS-CoV-2]. But, some viruses can be transmitted between mammals relatively easily, so there’s no way to tell whether there is another animal where these two viruses perhaps co-existed. More surveillance is necessary.”

Research gathers global momentum

Announced on the same day that Daily Maverick reported on the Baylor College findings, additional preliminary findings by a team of 26 researchers from South China Agricultural University had also found correlations between pangolin and SARS-CoV-2 RBDs.

This university’s detailed findings, posted on the bioRxiv forum on 20 February, made global headlines but have been challenged by some scientists.

However, since Baylor College emerged as the first academic team to share their seminal comparison study on bioRxiv on 13 February, at least 11 additional independent Australian, Chinese and US studies exploring pangolins as possible intermediate carriers have been made public on this very forum.

At the time of writing, the Baylor College and South China Agricultural University preprints had soared to the 99th percentile of some 15 million research outputs ever monitored by the forum’s global “attention tracker”.

And the other preprints — none of which were peer-reviewed when posted to the forum — generally agree:

- Pangolin coronaviruses appear to be genetic kin of both SARS-CoV-2 and bat coronaviruses.

- Since pangolin RBDs seem most closely related to SARS-CoV-2, this suggests not only a recombination event between pangolins and bats at some point during the virus’s evolution, but that pangolins may be more infectious to humans than bats.

- Bats still appear to be the original reservoir host, but pangolins are the likeliest intermediate vector yet.

In their conclusions, all preprints urged further research.

“Indeed, the discovery of viruses in pangolins suggests there is a wide diversity of coronaviruses still to be sampled in wildlife, some of which may be directly involved in the emergence of [SARS-CoV-2],” said researchers in yet another bioRxiv study, this time by Chinese and Australian institutions.

The preprints made other pointed recommendations, such as introducing urgent mechanisms to end wildlife trade; removing pangolins from wet markets to halt zoonotic transfer; and extensively monitoring pangolin virology.

“Large surveillance of coronaviruses in pangolins,” recommended another study by Chinese and US institutions, “could improve our understanding of the spectrum of coronaviruses in pangolins.”

Big academia weigh in: it is NOT biological warfare

Wild and unsubstantiated conspiracy rumours have been floated about the genesis of the virus, including that it escaped from a Wuhan laboratory — but a paper published in Nature Medicine last week thoroughly debunked this.

As a peer-reviewed paper in one of the world’s most respected journals, it also added authority to the hypothesis of pangolins as a likely intermediate vector.

The paper, by Australian, UK and US institutions, attributed the virus origins to zoonotic transfer from an animal, possibly arising in the Rhinolophus affinis bat and then spilling over into a pangolin.

“It is possible that a progenitor of SARS-CoV-2 jumped into humans,” they report, “acquiring the genomic features described above through adaptation during undetected human-to-human transmission. Once acquired, these adaptations would enable the pandemic to take off.”

Will pangolins come and save us?

“In the midst of the global Covid-19 public-health emergency,” the Nature study offered, “it is reasonable to wonder why the origins of the pandemic matter.”

But they do matter.

“The trade in and consumption of wild animals is not only an animal welfare issue, it’s a human rights travesty as attested by a pandemic that has brought the world to its knees,” said Audrey Delsink, wildlife director at Humane Society International in Africa.

“Detailed understanding of how an animal virus jumped species boundaries to infect humans so productively will help in the prevention of future zoonotic events,” the Nature study concluded. “If SARS-CoV-2 pre-adapted in another animal species, then there is the risk of future re-emergence events.”

Peter Knights of international conservation organisation WildAid warned that pangolins, among the world’s most endangered and trafficked mammals, are highly pathogenic.

“Whether or not Covid-19 is found to have been transmitted through pangolins, it certainly could have been — and, if current levels of illegal trade continue, they could be a vector for another new disease. Pangolins have high pathogen loads and carry parasites, like ticks. They are also massively stressed, malnourished and dehydrated when in trade,” said Knights, who in recent years has had success working with the Chinese government to reduce the consumption of shark-fin soup by a reported 80%.

Scientists may have mapped only a fraction of wildlife viruses, which have co-evolved in a staggering variety of insects and animals — not just pangolins and bats.

The majority of known emerging infectious diseases — especially viruses — are of animal origin, said a Royal Society paper by scientists from Cambridge University, London’s Zoological Society and EcoHealth Alliance. The proportion of those emerging from wildlife hosts, they noted, increased substantially over the 20th century’s last four decades.

This underlined the urgency of redrawing the architecture of medical science to join holistic dots between public health, non-human life, the hidden costs of economic development and degraded ecosystems, which biodiversity scientists warn are a hotbed for emerging infectious diseases. Our relatively poor understanding of the extent of disease in wildlife shows that the virology-research vessel may have hit only the tip of the iceberg and, to conservationists like Knights, this makes the trajectory of emergency response obvious, not just in China, but in other key regions of the human planet.

“All governments with bushmeat and wildlife consumption primarily in South East Asia and West and Central Africa should review their legislation, penalties, enforcement efforts and public awareness of the risks at this time. All live wildlife markets should be closed around the world,” he urged.

It seems African governments may be following suit. Last week the Nyasa Times reported that Malawi would ban the sale and consumption of bushmeat. A mass Covid-19 “sensitisation” campaign would follow.

Knights cautioned: “It’s obvious that some species should not be allowed to be consumed at all, while there may be some ‘safe’ species: like rabbits, quail, some deer and antelope and grasscutters.

“As we add species of conservation concern or health risk, the banned list gets longer and longer. Instead, we should be looking at a short ‘clean’ list of animals that can be legally consumed and enforced, and the public [will] know that everything else is off limits.” DM

* “Troy cell” is used metaphorically to illustrate an example. It’s not meant to be used or interpreted as a scientific term.

Original source: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za

by Noah's Ark | Mar 25, 2020 | Climate Change, Global |

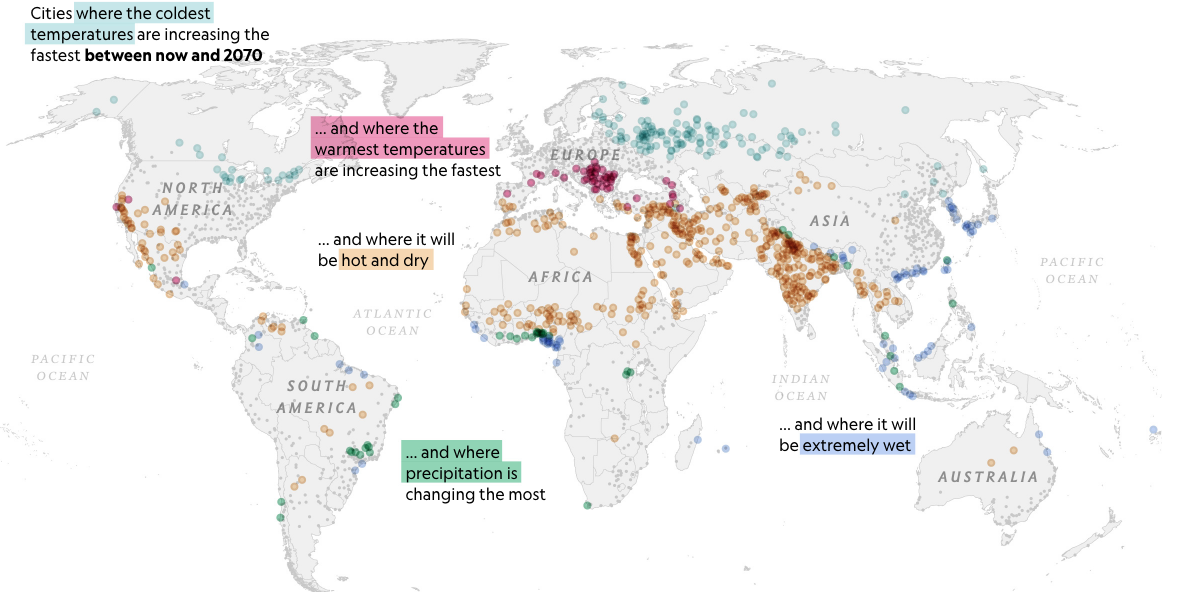

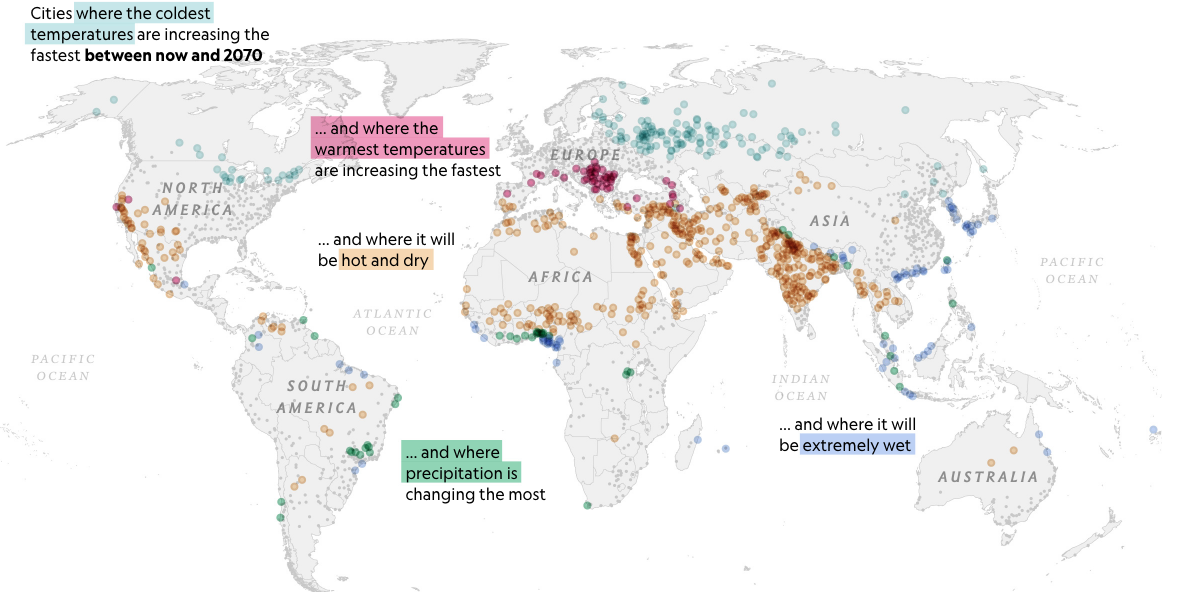

The whole planet will feel climate change’s impacts over coming decades. But some cities will see more dramatic changes in temperatureor precipitation than others.

More and more of us live in urban areas. Today, some 55 percent of the world lives in cities, and a quarter of all humans live in the 2,500 most populous cities. That percentage is expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades. By 2050, as the global population swells and urbanizes, about 70 percent of people will live in metropolises.

Earth’s climate, meantime, will continue to change in response to ever-rising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. Further warming will induce dramatic changes in nearly every corner of the planet. Some of those effects are already playing out.

Many of the impacts of future warming will be felt by the growing population of city dwellers. Cities concentrate people, infrastructure, activity, and many other resources into tight spaces, which means they’re particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Hotter temperatures put extra stress on human bodies, asphalt-covered roads, and more; more intense droughts can tax water systems; more intense rainfall can flood cities’ drains.

National Geographic partnered with University of Maryland climate scientist Matt Fitzpatrick to look at how temperature and precipitation patterns in many of the major urban areas of the world could change by 2070 if significant efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions are not made quickly—the “RCP 8.5” scenario.

The conclusions are clear: Just about everywhere in the world will experience shifts in seasons, hotter highs, and more extreme wet and dry periods. Some urban areas will feel more intense changes than others. But the alarming predictions are not set in stone. Today’s decisions can still influence tomorrow’s experience.

Warmer warms

Cities are affected more than rural areas by increasing air temperatures because they’re already hotter. Concrete, steel, wood, and other infrastructure materials trap more heat than a natural landscape does: the so-called urban heat island effect.

Unchecked climate change will drive temperatures up dramatically in every one of the 2,500 locations studied. During summer, the highest high temperatures are projected to increase by an average of 8 degrees Fahrenheit by 2070. In some places, the heat will be even more extreme. Summer temperatures in Urmia, Iran, for instance, will experience a 15-degree uptick, with average hot temperatures hovering at 98 degrees Fahrenheit.

Currently, only 9 percent of the cities studied have summer maximum temperatures that exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit, but that number will more than double by 2070. Among those future cities experiencing intense heat will be Grand Junction, Colorado, where today’s summer maximum temperatures of 90 degrees are projected to hit 100 degrees in 2070.

Cold seasons get less cold

The hot parts of the world are getting hotter, but some of the more dramatic changes are already happening—and will continue to unfold—in the places that are supposed to be cold. In general, the cold seasons in these places are warming up more quickly than warmer places’ warm seasons. The Arctic, for example, is heating up roughly twice as fast as the world on average, and its winters are taking the brunt of that warming.

Cities in the Far North will continue to feel their winters warm, if no major climate-curbing actions are taken soon. Among the 2,500 cities studied, the average minimum temperatures during winter are expected to increase 7.3 degrees Fahrenheit between now and 2070.

That’s enough to push some places over a dangerous tipping point from freezing into not freezing; snow to rain; ice to liquid; permafrost to sloppy, carbon-releasing mud.

The effects could be devastating. Snow that falls in the mountains of the western United States, for example, acts as a “water tower,” melting slowly through the spring and summer, providing water to areas downstream. If that snow falls as rain, the threat of later-season drought increases. Many agricultural crops, like almonds, wine grapes, and peaches, require a chill to produce fruit. Freezing temperatures also kill off pests, such as mosquitoes, ticks, and beetles, so warming winters could amplify the spread of vector-borne diseases and facilitate the earlier emergence of adult mosquitoes.

Cities outside the Far North will also see their cold seasons change. Today, 36 percent of the cities analyzed experience minimum winter temperatures below freezing. By 2070, 62 percent of the cities analyzed will no longer have below freezing winters.

What’s happening to the rain?

Another likely outcome of climate change is that the subtropics—regions just north or south of the tropics, such as northern Mexico or the Argentinean Pampas—will get drier. In general, higher latitudes are predicted to see more total precipitation, particularly rainfall, as the Earth warms. Exactly how those changes will play out seasonally is harder to pin down, though.

All in all, we should expect “more intense but less frequent precipitation,” says Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA, with longer dry stretches between rainfall events.

Some cities that will experience drying will be better equipped to handle it than others, Fitzpatrick says. Places that already get abundant rainfall will be less strapped by a 20 percent decrease than somewhere that’s already really dry.

“A 20 percent decrease in an area that already has marginal rainfall,” he says, “very easily could transition it to a place with significant water issues.”

For every one degree Celsius the air heats up, the atmosphere holds 7 percent more water vapor. That means that by the end of the century the atmosphere will be able to hold 27 percent more water vapor than it does today. Adding that much more precipitation into the world’s water cycle will create more intense rainfall, particularly escalating the risk of flooding.

Much of the change is likely to occur during the cooler months of the year: 812 cities will have almost no precipitation, but many others will have extreme precipitation. And while many of the most extreme cities will get drier,11 cities across Nigeria, Rwanda, and Cameroon will also experience significantly more precipitation in 2070.

Original source: https://www.nationalgeographic.com

by Noah's Ark | Mar 24, 2020 | Climate Change, Global, Natural World |

When the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, societies may adopt some important measures that would lower emissions, from more teleconferencing to shortening global supply chains. But the most lasting lesson may be what the coronavirus teaches us about the urgency of taking swift action.

A frightening new threat cascades around the world, upending familiar routines, disrupting the global economy, and endangering lives. Scientists long warned this might happen, but political leaders mostly ignored them, so now must scramble to respond to a crisis they could have prevented, or at least eased, had they acted sooner.

The coronavirus pandemic and the slower-moving dangers of climate change parallel one another in important ways, and experts say the aggressive, if belated, response to the outbreak could hold lessons for those urging climate action. And while the dip in greenhouse gas emissions caused by the sharp drop in travel and other economic activity is likely to rebound once the pandemic passes, some carbon footprint-shrinking changes that the spread of COVID-19 is prompting could prove more lasting.

Both the pandemic and the climate crisis are problems of exponential growth against a limited capacity to cope, said Elizabeth Sawin, co-director of Climate Interactive, a think tank. In the case of the virus, the danger is the number of infected people overwhelming health care systems; with climate change, it is that emissions growth will overwhelm our ability to manage consequences such as droughts, floods, wildfires, and other extreme events, she said.

With entire nations all but shutting down in hopes of slowing the viral spread, “the public is coming to understand that in that kind of situation you have to act in a way that looks disproportionate to what the current reality is, because you have to react to where that exponential growth will take you,” she said. “You look out the window and it doesn’t look like a pandemic, it looks like a nice spring day. But you have to close down all the restaurants, the schools.”

The virus has shown that if you wait until you can see the impact,

it is too late to stop it.

While the disease is playing out more quickly than the effects of global warming, the principle is the same, she said: If you wait until you can see the impact, it is too late to stop it.

“COVID-19 is climate on warp speed,” said Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at New York University and co-author of Climate Shock. “Everything with climate is decades; here it’s days. Climate is centuries; here it’s weeks.”

Governments’ responses have morphed almost as fast as the threat. French President Emmanuel Macron ordered all non-essential businesses to close barely a week after spending an evening at the theater with his wife. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio made similarly abrupt shifts, and President Trump pivoted from downplaying the virus’s dangers to backing measures that had seemed unimaginable shortly before.

“We are watching our political leaders learn these lessons live on TV, within days,“ Wagner said. “That’s a learning curve we have never seen with anything, at least not in my lifetime.”

Now, he said, politicians who have grasped the terrifying power of compounding growth must apply that new understanding to the climate.

And as with the coronavirus, said Wagner, climate policies must push everyone to take heed of the costs their actions — whether disease exposure or carbon emissions — impose on others. “It’s all about somebody else stepping in and forcing us to internalize the externality, which means don’t rely on parents to take their kids out of school, close the school,” he said. “Don’t rely on companies or workers to stay home or tell their people to stay home, force them to do so or pay them to do so, but make sure it happens. And of course that’s the role of government.”

Stimulus measures aimed at easing COVID-19’s economic shock could aim to drive emissions reductions too, by funding low-carbon infrastructure or offering online training for green-economy jobs to newly unemployed workers stuck at home, Sawin said. Fatih Birol, director of the International Energy Agency, last week similarly urged governments and international financial institutions to incorporate climate action into their stimulus efforts by funding investment in clean power, battery storage, and carbon capture technology.

In Sawin’s view, the pandemic’s multi-layered impact supports an argument U.S. Green New Deal backers have been making: Tackling our biggest problems in tandem may be more effective than taking them on one at a time. Just as those without sick leave may spread the virus because they must work while infected, unaffordable child care and an employer-based health insurance system can rob people of the flexibility to relocate for jobs in growing industries like clean power, she said. “People are starting to understand that to have a whole society shift behavior really quickly, you need to support everyone,” Sawin said. “A social safety net reduces the friction of change.”

Another parallel between the two crises is that we could have headed them off, said Michele Wucker, author of The Gray Rhino: How to Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore. The book’s title is the metaphor Wucker uses for a high-probability, high-impact event, a counterpoint to the popular idea of a black swan, the term writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb coined for a very unlikely but highly damaging event that is by its nature hard to foresee.

Voters reward politicians for fixing problems,

but rarely for preventing them.

Both viral spread and climate change are gray rhinos, Wucker said — “the 2-ton thing that’s coming at you, and most of the time we downplay it or neglect it. We kind of miss the obvious.”

The Trump administration, which has aggressively rolled back measures meant to reduce carbon emissions, also axed the National Security Council’s global health security office and sought to cut funding to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And, like many other countries, the United States did little to ramp up coronavirus preparations even as the disease ravaged China.

Wucker said there were political, structural, and psychological reasons for such inaction. “Heading off a risk is risky in and of itself,” she said. “People are afraid of doing the wrong thing,” more than they are of doing nothing. Voters reward politicians for fixing problems, but rarely for preventing them, giving leaders incentive to kick knotty issues down the road.

And powerful interests are vested in maintaining the status quo, she pointed out. That dynamic has been central to the global failure to act on climate, with the fossil fuel industry funding a decades-long effort to cast doubt on climate science, and lobbying to thwart changes that would threaten its profits.

In the case of COVID-19, while some have sought to deny the seriousness of the coronavirus, people and governments have mostly been far quicker to appreciate its danger. That may in part be because we are instinctually more frightened of disease than of climate threats that many people struggle to envision, Sawin said.

More importantly, though, “one of the richest industries in human history [fossil fuels] isn’t trying to prevent people from understanding” the coronavirus, she said.

The global response to COVID-19 — a near halt in international aviation, factories closing in China and elsewhere, a panicked scramble to enable remote work — will almost certainly bring a downward blip in carbon emissions.

But such changes are likely to be temporary, with emissions from driving, for example, expected to bounce back as soon as people return to workplaces. If many grow fearful of public transportation, commuting’s carbon footprint might even rise further, experts say.

But some new behaviors could outlast the pandemic, including carbon-cutting shifts climate activists have sought for years. The changes most likely to stick in such a crisis are those that were already underway before it hit, said Amy Myers Jaffe, director of the Program on Energy Security and Climate Change at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“The question is what trends were out there that could now happen faster,” she said. At the top of the list, Jaffe believes, is a fall in business travel, as big companies realize video meetings can often accomplish as much as in-person ones.

Similarly, she said, the pandemic may hasten a flattening, or even reversal, in the growth of international trade, which began to slow in 2019 because of tensions over tariffs. “Now, of course, it’s really crashing,” Jaffe said. If virus-induced shutdowns or border closings create shortages of drugs, medical equipment, or other essential items, many nations and companies may be anxious to reduce their vulnerability to highly globalized supply networks. “If we shrink supply chains, if countries are going to produce more of their own goods, I think that is structurally going to reduce oil demand” and shrink shipping’s carbon footprint, she said.

A shift toward remote working may also be here to stay,

with some companies abandoning offices altogether.

A shift toward remote working may also be here to stay, said Prithwiraj Choudhury, an associate professor at Harvard Business School. And it doesn’t just mean workers logging on from home in the same city as their company. It offers the freedom to work from anywhere — in a small town with a lower cost of living, for example, or wherever a spouse’s job is, he said. Some companies and organizations have gone completely virtual, abandoning offices altogether.

“There’s a lot of latent demand” among workers for such arrangements, and companies may welcome the change as they realize they can save money by maintaining smaller offices, or none at all, Choudhury said.

Those workplace changes may bring real emission reductions, but Sawin said the pandemic’s most important climate impact could come from people applying the lessons the coronavirus teaches about the urgency of swift action.

When the outbreak finally ends, “if we can tell that story of what we just went through and help people understand that this is an accelerated version of another story we’re going through that has the same plot structure but a different timeline, that could be transformative,” she said.

No one could celebrate a disease spreading so much fear and suffering, Sawin emphasized, but with the losses inflicted by the coronavirus sure to mount, “maybe there’s a kind of honoring of that, to at least take what we learn and put it to good use.”

Original source: https://e360.yale.edu